More Economies of Scale: Efficiency, Head Count and TCO

James Hamilton’s presentation at Mix 10 illuminated cloud computing economics that few others have direct experience with, but I also believe that this presentation raises interesting questions that didn’t get addressed. (If you haven’t seen James Hamilton’s Mix10 presentation, go watch it now. You should probably also go through Randy’s follow up, and then watch James talk again… I’ve watched it 3 times now.)

This is the first post that will refer to aspects of James’ talk (and I plan at least one more about business models) and in case I haven’t stressed this enough, if you have any interest in understanding the economics of cloud computing, take the time to watch one of the best in this business.

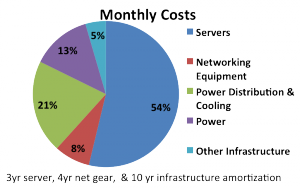

Central to James’ presentation is the breaking down the total cost of ownership of computational infrastructure. His breakdown is based on his own data running web scale services and he provides us with a great analysis on the inevitability and sustainability of cloud computing business models. One of the key points James makes is that the only variable cost in the chart is the cost of power.

Cost Breakdown from James Hamilton

Cost Breakdown from James Hamilton

The thing I want to focus on here is the missing cost of personnel. James touches on this at different points discussing administration and automation. He gives out the number ‘as low as 3% for services’, so I’m assuming he is burying this as a negligible cost. I would argue that this cost is actually highly variable, and, while correlated with scale, is also a function of the types of services an organization provides and how those services relate to the core business. Additionally, automation investments can be scaled down effectively, but that’s what I’ve been working on for a couple years so this is likely a reflection of my bias.

Based on James’ biases (which he is straightforward about), that the cost of personnel can be driven down to almost nothing is essentially taken for granted. I contend, based on personal experience and observation, this is still a significant operational cost for many organizations. I would take this a step farther and posit that the level of efficiency James refers to only comes from the crucible of running web services at scale with considerable economic pressure for little or no downtime. Furthermore, this level of efficiency and cost reduction will never materialize in organizations who view IT as a cost center. Efficiency doesn’t just come for free, at scale or otherwise.

To keep the numbers easy, let’s assume an admin is paid $100,000 per year. Then neglecting the aspects of networking and storage, that admin can manage some number of machines. If that number is 100, then managing each machine costs $1000 per year or ~$83 per month. If that number is 1000 machines, then each machine costs $8.33. If those are $3000 servers and the servers are roughly 54%, then if I’m understand correctly the $8.33 is around 5% of the monthly cost when amortized over 3 years. James gave us price or efficiency ratios for storage, networking and admins. For a large service he listed ‘over 1000 servers/admin’. He did not give us a ratio or a price point per server, but in order to get down to ~3%, the admins need to manage significantly more than 1000, the server cost is significantly higher than $3000, or the admins get paid significantly less than $100,000. (this also assumes salary is the only cost and nothing is paid for any management tools…)

What do you pay your admins? What do you pay for servers? What is the ratio between them?

Which one do you have the most control over?

(hint: the way to optimize the ratio is not to hire less admins, unless your customers like down time…)

Watching the evolution of the cloud computing landscape, in the rush to bring new services to market or transition away from apparently disrupted business models, I believe many organizations may unnecessarily learn this lesson the hard way. The proper care and feeding of the infrastructure better be a core competency for those who intend to compete ‘as a Service’ at any level. The operational differentiators have as much to do with process and culture as they do with technology, but doing them well could be the difference between business success and failure. I believe this is difficult to retrofit, especially at scale.

So what should you do? Start by trying to understand what your costs look like today, and I’ll follow up with perspectives and resources that might help with operational efficiency, at any scale. Operations can be a competitive advantage, but only for those organizations who have made the investments in both the people and the infrastructure.